Why is your company not a simple field?

Strategy must precede planning!

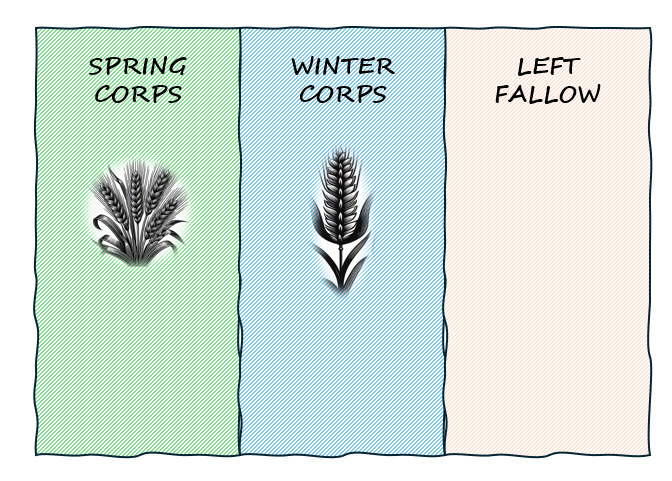

The three-field system was a traditional farming method widely used in medieval Europe, especially from around the 9th to the 15th century. At its core, the method was about dividing the field into three parts. The first one was dedicated to spring crops such as barley, which were sown in spring and harvested by the end of summer or early autumn. The second part was used for winter crops like wheat, planted in autumn and harvested in the following spring or early summer. The third section of the field was left fallow, meaning it was not used for cultivation during this cycle.

Every year, farmers would rotate the crops among the three sections, as it allowed the land to be used more efficiently. This approach led to more crops being grown, which was crucial as Europe's population increased during the Middle Ages. Rotating crops like this also helped the land recover better and lowered the chance of the soil wearing out.

It was an excellent method for "maximizing" the potential of the owned land - perfectly suited to the requirements of that era.

Unfortunately, many companies these days are inspired by this approach and follow it to a tee in managing their businesses.

Planning that leads you astray

Let's imagine for a moment that you're in Milan, serving as the CEO of an industrial market company. You specialize in the design of physical products and based on feedback from numerous customers and industry analyses, your company is recognized as a market leader in this sector. The end of the fiscal year is approaching with big steps, and while many are already thinking about a ski trip, your thoughts are in a very different place - you need to plan the budget for the next 12 months.

How do you do this?

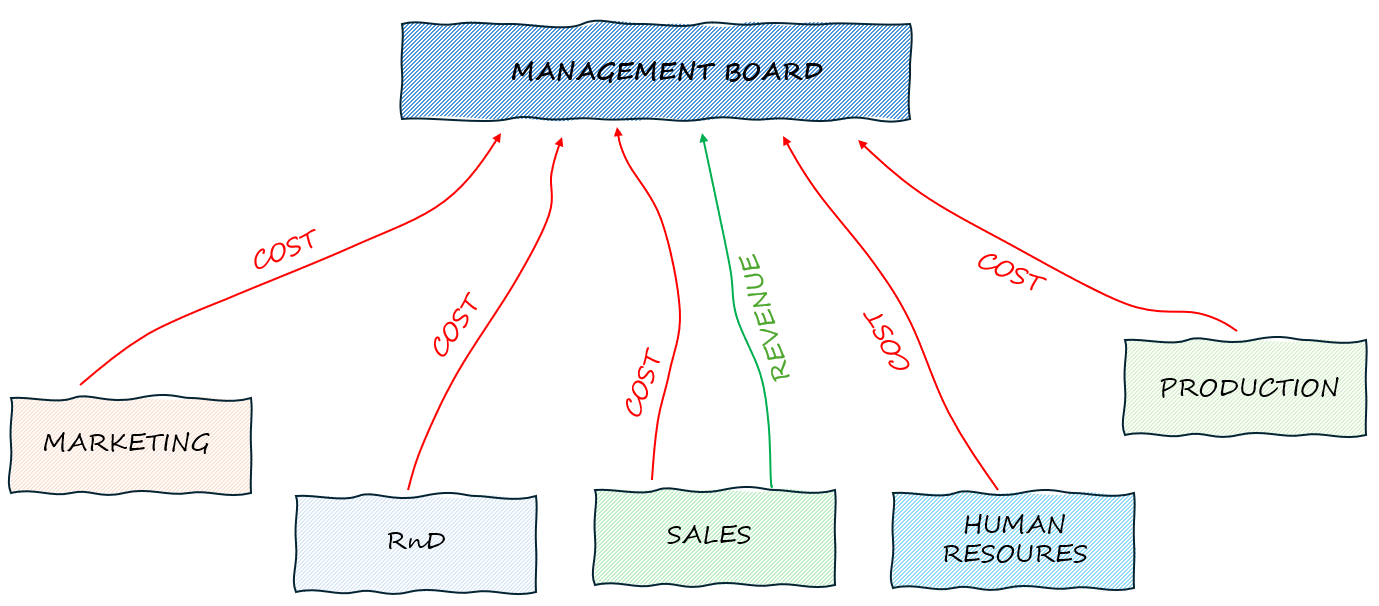

Well, the company may not be a huge corporation, but it’s large enough that knowing all the nuts and bolts of each area of the business is impossible. You’re not sure what specific needs might arise in each department. So, you ask your finance team to prepare an Excel file and send it to every department head to fill out.

Your main question is about the cost, but you ask it in a more sophisticated way:

What do you need?

How much will it cost?

And why do you need it?

As a result, from each department, you receive: “I want X, because of Y, and it costs Z."

Parallel to getting these answers, you're also engaged in a discussion with the sales department, attempting to understand how much revenue they can generate from the market.

If you distill these activities down to their essence, they essentially boil down to planning the allocation of your available or forecasted budget among different departments:

By combining the totals of "What do we need?" and "How much will we get?", we believe we obtain a complete view of the upcoming future, or at least the year ahead.

If at the end of this simple number math, we have a positive result (profit), you can rest assured and go on your long-awaited vacation. However, if the end result is flashing red - spending cuts will be necessary (usually without giving it much thought and equally across each department).

From a broader perspective, your job essentially involves managing existing resources, or more specifically, planning their distribution among the various departments in your company.

So in a way, you become a "medieval farmer", who planned each year which part of the field should be sown with which seed.

Now, without a shadow of a doubt, they were very hardworking people, but their “planning reality” was not too complicated. They already had a working strategy that ensured the maximization of resources. Their actions were confined to dividing the field into three parts and following a rotational process: sowing barley in one section this year, wheat in the next, and then leaving it fallow.

Unfortunately, for the vast majority of us, the reality we live in, is completely different - much more complex and multidimensional, with various forces we have no control over.

You cannot plan if you don’t know what you are trying to accomplish, what obstacles you need to overcome, and by ignoring the resources you possess.

Planning, in fact, should be the last stage of work on the strategy, as it’s actually the distribution of tasks between different people/departments.

Doing it without first crafting a strategy makes no sense, and here’s why:

Misalignment:

Let’s come back to the planning exercise you’re performing as a CEO in our previous example.

In many cases, examining the budgets from each department reveals that they are often extrapolations of the previous year’s allocations. So, you simply take those figures, add an extra 10% for each activity, and voila – you have a budget for the next year, a classic example of the 'peanut butter' concept in practice.

If you don’t have a clear view of how you’re going to achieve your goals/approach challenges you have - you may end up “financing/pursuing activities within each department that don’t support your overall goal (or what’s even worse - they create internal initiatives that contradict each other).

Focus on a narrow perspective:

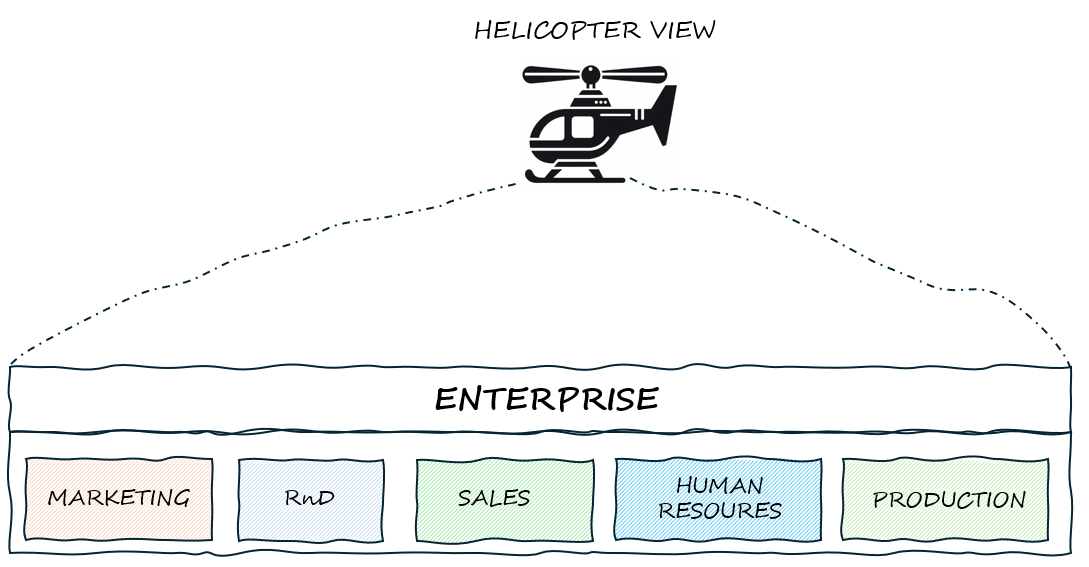

A frequently heard term among executives during planning is "helicopter view." Essentially, this means adopting a wide-ranging perspective of the entire company, akin to observing from a helicopter's altitude.

Initially, this approach seems logical as it allows you to observe all components below, clearly understanding how they are connected and how they influence each other.

The primary issue with the 'helicopter view' in business strategy is that it often doesn't go high enough. While this perspective allows a comprehensive look at your company's internal operations, including inputs such as order reception and outputs like delivering services or products to customers, it unfortunately falls short.

This approach is limiting as it tends to overlook the wider market landscape in which your company operates.

For example, think about the effects if your competitors decide to significantly lower their prices to get more customers. Or picture a situation where the market starts to shrink because what customers want has changed. Also, what if new regulations come in that reduce your profits, making it hard for your business to survive?

These are key things to think about that a 'helicopter view' focused only on your company might overlook.

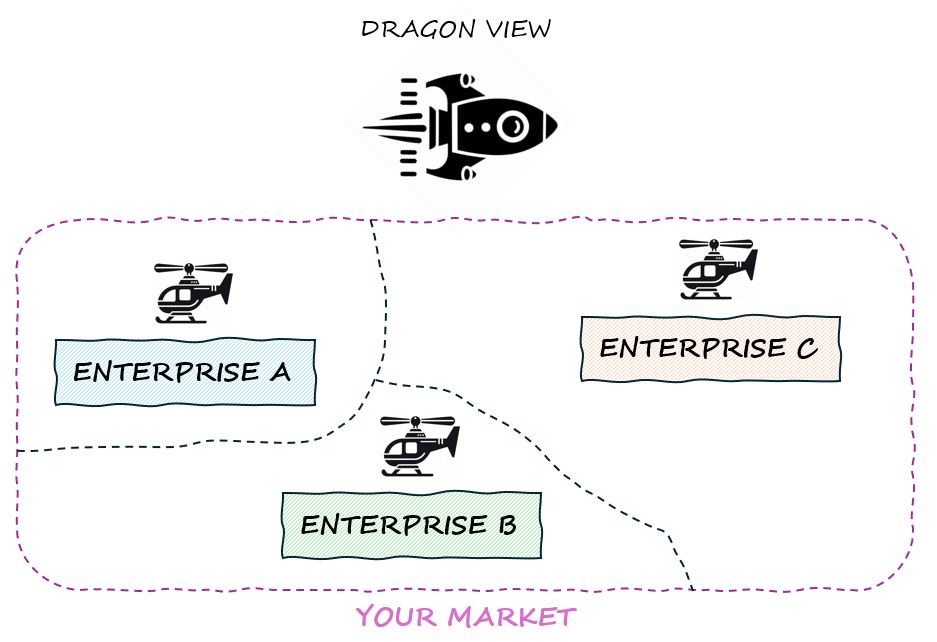

To fix this problem, you need to look at things from a higher level. You need a view that goes beyond what you can see from a helicopter, one that covers not just your company, but the whole market.

Think of it like getting on a spaceship, like SpaceX's Dragon, which takes you up high where you can see everything happening in the market. From up there, you learn a lot about where your company stands and how it relates to the bigger picture of the market.

This 'Dragon view' helps you make plans that really cover everything, considering both what happens inside your company and what’s going on in the market outside.

Focusing on the “here-and-now”:

In planning, we often zero in on the most pressing needs of the moment.

Consider a scenario where you have $1000 to update your wardrobe. Since you can't buy it all, you prioritize. Usually, this means addressing immediate needs rather than taking a holistic view of your wardrobe. For instance, buying discounted winter wear in spring might be more practical than getting a new spring jacket, especially if the one you have is still in a good shape.

Similarly, in the business world, resource allocation often centers on immediate challenges. This typically involves tackling current problems without much thought for future implications.

If the increased workload in your RnD department is only temporary, lasting about six months, hiring a new engineer might not be the wisest choice. A better solution could be engaging a contractor or agency to manage this short-term spike in work.

Generally, when you broaden your perspective to consider longer-term effects, your decision-making process differs significantly from when you focus solely on the immediate needs.

Planning offers a sense of control – you oversee expenses and determine how to allocate funds. It's a familiar exercise, part of our daily routine. We plan our meals, schedule meetings, and organize weekend getaways or vacation trips.

This definitely worked great for medieval three-field systems, but doint it without any strategic context can lead to disastrous outcomes.