What market are you really in?

Do the Work Most Skip

"The market is incredibly huge and even if we only capture a small portion of it, the revenue will reach at least 40 billion dollars, and within a few years, we could become the second Facebook."

These or very similar claims can be heard in the vast majority of presentations given during various startup competitions. I totally get it. As founders or persons responsible for sales and business development, we want to stir the imagination of possible investors. We want to convince them that it’s worth investing in our company. That is especially true when our existence is hanging by a thread - there are 50 people on your payroll, and a bank account is shrinking at a dizzying pace.

But that’s not only startup world. These kinds of 'analyses' can also be found in the corporate world, where well-established companies evaluate whether or not to enter a new market.

The problem is that most of these evaluations or brave claims are very far from the truth and usually backed up by a three-minute web search where we pick up the first value we find in a random article that pops up in our browser. It may sound funny, but you would be surprised how much this image closely mirrors reality.

There's also a second part - those who don't even try to ask themselves this question (“If you focus on operational work and do it well - good things will happen” as they say).

Yes, the question “What market am I actually in?" is difficult, but avoiding answering it, doesn’t move us forward in any way. At the end of the day, knowing what market you operate in is essential to your strategy.

What is a “market”?

If you skim through the pitch decks of the vast majority of startups, you will definitely find a slide showing the potential market they're going to capture. It's usually presented in the form of a pie chart and looks similar to this:

Very often, the narrative accompanying it describes the entire circle as representing several trillion, and your piece is shown as a percentage of the whole. Of course, the percentage is usually pulled out of thin air, because there is often no real justification for why it's precisely 40% and not, for example, 15%.

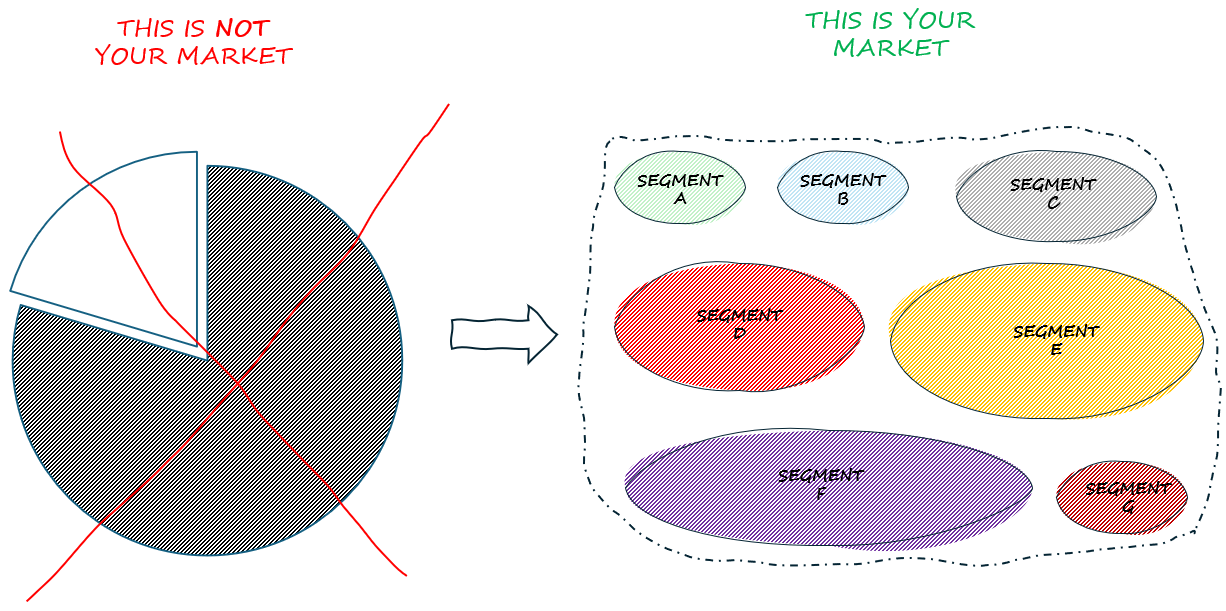

The problem with this kind of approach is, firstly, that the market doesn't resemble one big bucket filled with water from which I can pour a little into my bowl.

A 'market' is a set of buyers (individuals or companies) who have similar needs, goals, and limitations.

That's why, in practice, reality is much more complicated and looks as follows:

If you look at it and think about it for a moment, you will surely agree with the statement that, following this definition of the market, in our big bag, there are segments that might buy the same product, but for completely different reasons.

If you think about it even longer, you'll realize that, despite a particular segment needing your product, you might not be able to 'capture' that area (e.g., due to required certifications that your company is unable to meet).

Segments can differ in size and their exact needs (“why I buy this product”), geographic location (e.g. “I buy this product for the same reason, but I want to buy it in a local store and speak in my native language”), or constraints (e.g. “I can no longer afford weekend cinema outings with my wife because we recently had a baby”).

The ability to 'slice up' the entire market and justify your approach is necessary, and working on this aspect will certainly pay off.

If you understand each segment and the differences between them precisely, you will be able to focus. For instance, you can tailor your specific marketing message (and medium) to a specific customer segment.

By the same token, you'll know that a certain segment is still beyond your reach, because you can't afford a local presence in a particular geographical area.

This increases your efficiency and ensures that steam does not escape through the whistle.

Market metrics - how many of these dollars can I really catch?

Another benefit of taking the time to deeply understand your market is grasping what we are actually fighting for - what the business potential is. This potential is often presented in the form of three metrics: TAM, SAM, and SOM - each further specifying how much money we are actually able to extract from the market

Let's begin with TAM - Total Addressable Market. This is the total market demand for a product or service. It's the maximum amount of revenue a business can possibly generate by selling their product or service in a specific market. It assumes a 100% market share and is useful for understanding the potential of a market at a high level. As a business owner or investor, you need to understand what is the maximum of what you are fighting for.

This is a useful piece of information, but more business-savvy people require delving a level deeper. This is because the guy serving hamburgers in Manhattan might say that his TAM is the entire food market.

While of course this is technically true, it's completely nonsensical in the context of business analysis. After all, even kids in 11th grade would understand the guy won’t be able to sell that many hamburgers and serve them to people on the other side of the world.

That’s why we go a little deeper and say, “OK, while definitely there are many people across the globe who are hungry, but you can serve your hamburgers only to people who are in Manhattan. What significantly narrows down the market for your business.

This is how SAM - Serviceable Available Market - is created. This is the segment of the TAM targeted by your products and services which is within your geographical reach. It's a more realistic assessment of the market that a company can actually serve with its current business model, distribution channels, and products. It is a much more realistic figure regarding the current capabilities of your business.

Now, it wouldn’t be a stretch to imagine that there appear a few more burger stands on Manhattan. Suddenly, you are not the only option. You have to face competition that might have lower prices, better marketing, or a loyalty program that encourages buying there.

This is how SOM (Serviceable Obtainable Market) is formed, which defines what portion of the previously defined SAM we are able to capture. It is a figure that shows in the most concrete way how much our business can generate.

Once you divide your entire market into various segments, it's useful to analyze them through the lens of these metrics. Can you convince someone to buy without a local presence? Is there high competition in all segments? Maybe some of these segments are very resistant to change, while in others it's quite easy?

How do I know what market am I really in?

It doesn’t matter what you think about yourself. However, it does matter what and how your customers think about your product or service. It is important because they will compare your offer or service to other things they can use. That’s why one thing to remember is that your customers define your market, not you.

So, in order to understand the space you’re competing in, ask them:

“If I didn’t exist what else would you choose?”

The answer you get may be refreshing and sometimes sobering, as you would have never thought about how your product is classified in your customer minds.

Take, for example, a million startups claiming to exist in the artificial intelligence market, which is growing at an alarming rate. Suppose you have created a CRM system for medium-sized manufacturing companies that uses certain elements of AI technology - say, to give salespeople insights on when it's worthwhile to contact a potential prospect. If you ask your customers what market you exist in, will they really classify your product as part of the AI market? No. For them, you will be competing with other CRMs dedicated to medium-sized manufacturing companies. Your AI may be part of the unique value you deliver to customers, but your product is not part of the AI market - only CRM systems.

How many startups would save a lot of money a if they asked this simple question?

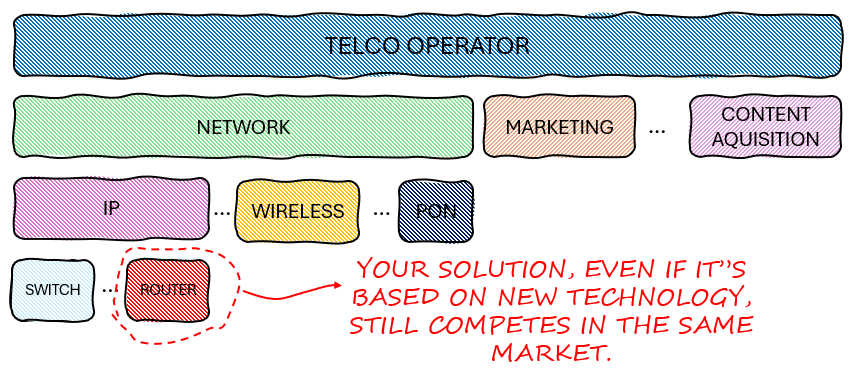

Another great example is virtualization that became a significant trend in the IT industry mainly in the early 2000s.

People looked at custom-made hardware devices and said, "Hey, maybe we can use off-the-shelf devices and run specific software on them to create a product dedicated to your needs. The development of such products will be both faster and cheaper.

Thousands of startups jumped on this bandwagon, and wherever previously dedicated hardware was used, products began to appear with a standard “off-the-shelf servers” and special software.

When talking about themselves, they would say they are a "virtualization" or "software" company. But the truth was that their customers compared their software-based products to products based on dedicated hardware.

If your customer previously bought switches from Cisco that were made on dedicated hardware, then your switch, which used new technology, would still be compared with the value delivered by the old Cisco switch.

The technology for delivering value changed, but the market remains the same.

Artificial Intelligence and virtualization are technologies, tools that are used to deliver specific value to your customer. They exist in a solution space. Therefore, the fact that you use them in your product does not mean you are part of that market (unless, of course, you're developing another chat GPT and want to compete directly with OpenAI).

It's crucial to understand how your clients classify your solution. "What else would you choose?" is an eye-opening question that you should always seek answers to from your customers.

Now, sometimes it's not possible to ask such a question directly. In that case, I would advise making a list of your best customers and trying to find any patterns among them. Perhaps they are companies from a specific industry, of a specific size, or in a specific geographic location. Try to build a certain hypothesis around it and then look for any way to prove it.

The answer to the question of which market you are competing in is not simple. It often requires a moment of reflection and interaction with our customers. But understanding your own playing field is crucial for success. After all, you need to know who else, besides you, is competing in this area.

Ignoring and trivializing the work of understanding your market always ends badly.