Are You Pursuing an Opportunity or Building a Business?

A big client with a recognizable and respected brand calls you one day. He's facing a significant issue - for several months now, he has been searching for a device for his network that is unique enough that he cannot find anything that meets his requirements. With practically an unlimited budget allocated for this purpose, his management board consistently asks about progress in this matter every week.

You're as excited as a kid on Christmas morning. You've always dreamed of starting your own business, and here it is - the treasure chest has just fallen at your feet. You know exactly what to do and who to call to make it happen. John perfectly understands system-level requirements, and Steve is the guy who can definitely build a team to handle software development. It’s even better. The customer agrees to pay you half the money right upfront. No external investments needed – what a stroke of luck! You can now concentrate solely on developing a product that meets all your customer's needs.

So, you hire some smart folks and start working on the project. It takes a whole year, with lots of little bumps and hiccups along the way, but finally, you've got it! You show the device to the customer, and he is simply delighted. The proof of concept (PoC) is successful – the device performs admirably in its first real-world test. The customer is satisfied and gives you the green light to produce the agreed volume over the next 12 months. You sign a Service Level Agreement and prepare your service engineers to be ready for any potential issues.

Now, what next? You have a product that solves a need for the customer, so naturally, you say - hey, there definitely may be other companies that need the same device. So during one long afternoon, you prepare a few slides outlining a problem and your corresponding solutions. Let's sell it! Unfortunately, getting people to talk to you is not easy, and those who agree to talk don't have this particular problem or have already solved it differently. You come back to your old customer with a new proposition: 'Wouldn't you be interested in developing a new version of this device?' You think about adding additional features, changing the housing, or increasing throughput. But your customer is satisfied with the solution you provided and doesn't need any other equipment. After several months of 'trying harder,' you realize your bank account is melting as fast as icebergs in the Arctic. People sense this and start to leave - you're forced to shut down what seemed at the beginning like a fantastic venture."

What happened? Did you do something wrong? Not really. You simply seized the opportunity, but it wasn't enough to create a business.

Looking back, it's pretty clear why things didn't work out. First off, not enough companies or people were dealing with the same issue. And the second thing? The problem wasn't ongoing. Once we rolled out our devices, it pretty much disappeared. So there was no repeat business to bank on (or it wasn’t enough to maintain the company financially)

One school of thought suggests you shouldn’t care about scaling unless you have a customer who loves your solution, valuing it within the required price range. I agree with this to a certain extent, as you should initially give some thought to the broader market you are serving.

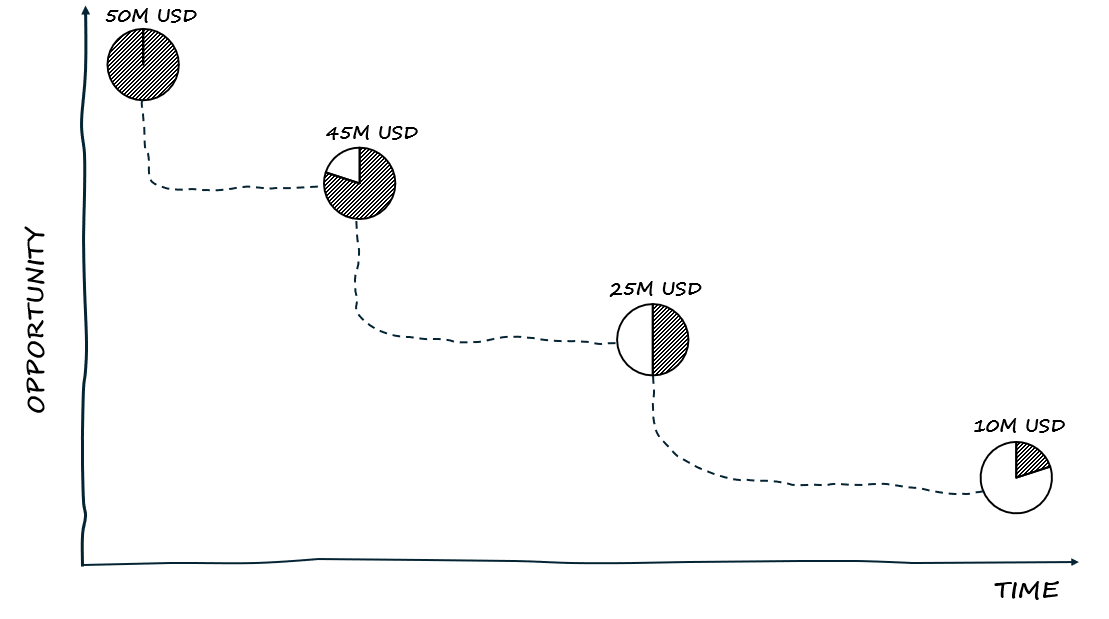

The difficult-to-detect problem arises when your revenue stream comes from an increasing number of short-lived opportunities, and you blindly focus on current business results without considering their implications for your future.

Unfortunately, these are things you often realize only when your sources dry up, and you start panicking to find ways to cover existing costs.

This is a common pitfall in the technology sector, where engineers, often enamored by the allure of technological innovation, may overlook the broader business context. It's not just about finding a client willing to pay for a technologically advanced solution; it's about identifying a larger client base that can sustain your business.

Another aspect to consider is the recurrence of the problem you're solving. Take, for example, seasonal businesses that operate only for a part of the year but generate enough revenue to sustain themselves year-round.

Similarly, consider companies that certify others – while the certification process is one-time, the need for recertification is recurring, providing a steady revenue stream.

Don't get me wrong - seizing opportunities is important and can lead to achieving various goals, such as revenue, references from new clients, or learning new technologies. However, you always have to keep in mind that the value we provide might be temporary and, from a certain time perspective, could be lost.

That's why, when analyzing a particular topic, I often ask myself the following questions:

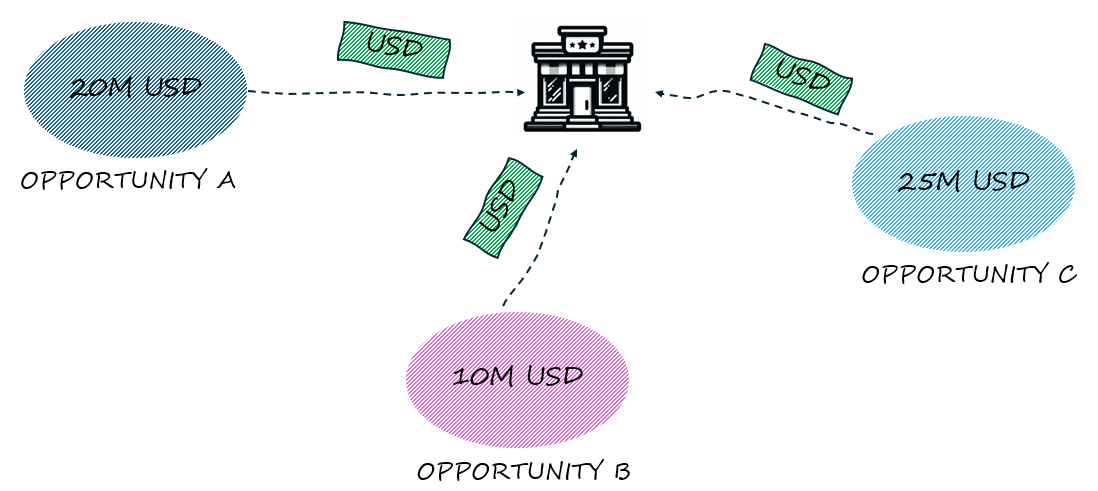

What is the scale of the problem I'm attempting to solve? In other words, what does the market for this problem look like?

Is this problem recurring, or is it resolved once and for all after being addressed?

Do people genuinely care about solving this problem? Are they willing to allocate resources to resolve it?

Can I address this problem within a specific budget?"

Remember, it’s not just about jumping on a cool opportunity. It’s about making sure it can keep going strong for a long time.